Don’t worry. I’m well aware of the fervent nerd-love that gets poured into this game on a daily basis. To settle any initial grievances: yes, I know that Final Fantasy 7 is ground well-travelled on the internet, and more to the point, that the 90’s were a long time ago. I’m also sensitive to the fact that any posthumous commentary on the game’s release will be a social minefield: no matter how well it goes down, someone will be driven to attempt grievous bodily harm. If there’s one thing that has come to define Final Fantasy 7, it’s the stark division between its fans and naysayers.

Today, it’s a territory I’m willing to brave.

Exactly fifteen years ago, Final Fantasy 7 was released in the western market: an event that has come to be recognised as one of the gaming industries’ few tried–and-true milestones. On September 7th 1997, Japan proved once and for all just how much fun can be had with a tub of hair gel and a comically oversized sword, and stopped along the way to redefine every major interactive experience going forward. Today is Final Fantasy 7‘s birthday, and thus I have an excuse to celebrate the only way I know how: with a great big wall of words. Proceed with caution.

It’s easy to forget how significant Final Fantasy 7’s release was for mainstream videogaming. The game’s release in America ushered in the broad acceptance of the RPG, and more than that, the dreaded J-RPG, all at once. It was the first non-Nintendo Final Fantasy title, and bolstered sales of Sony’s fledgling Playstation, practically guaranteeing the company’s lead in the console market for the generation to come. It cemented the idea of ‘cinematic’ gaming, and came to redefine the public’s perception of what a videogame narrative could achieve in terms of theme and scope. More generally, if the internet’s anecdotal evidence is anything to go by, it brought thousands of new people into the fold of videogaming, many of whom have stuck around to this very day. Say what you will about it these days, but back in 1997, Final Fantasy 7 (herein also referred to as FF7) was a critical and commercial powerhouse, the Pac-Man, or to borrow a more contemporary example, Grand Theft Auto of its generation.

To commemorate the 15th anniversary of the game’s release, I’m going to take a retrospective look at what FF7 got right, and try to consider how it holds up today. What made it such an important release, what missed the mark, and why are people still returning to play it to this very day?

Oh, but one last thing. Before I get started, I will admit that my judgement – like that of many my age – is inherently clouded by nostalgia. Videogames are personal experiences; Gordon Freeman isn’t important, neither are Croft, Strife or Crash – we’re the ones who battled our way through City 17, we’re the ones who outsmarted the Mudkon, stormed Dracula’s castle, and captured the bag twice in the same scout run, and I have no doubt that this is one of the main reasons why FF7’s popularity persists. Final Fantasy 7‘s fans are a wistful bunch, almost sickeningly so.

There are a whole generation of twenty-somethings out there who grew up in the slums of Midgar, racing Chocobos and cursing Sephiroth’s name into the sky; and all of them now look back on this game through rose-tinted glasses, sighing affectionately, as if they themselves had saved the planet from imminent destruction. I should know, I’m one of them.

I first played FF7 when I was noticeably shorter, back in the summer of ’98, and still have fond memories of plodding through the game for the first time with my brother, an experience that, if I recall correctly, took much longer than it should have, especially with a strategy guide in hand. I hold the memory close to my heart, right next to a weathered copy of The Land Before Time and a picture of The Brave Little Toaster. Final Fantasy 7 is so far divorced from the expectations of a modern videogame that it’s hard to reflect on it without sinking into a nostalgic stupor.

Speaking of that strategy guide…

Appropriately, the gnarled back-cover of that Brady guide is perhaps our best starting point when discussing Final Fantasy 7‘s popularity. If there was one marketing term above all others in 1997, it was ‘Full-Motion Video’ (FMV). Anyone who was even remotely invested in videogames in 1997 should be able to remember the 100 million dollar ad-campaign for Final Fantasy 7 – composed almost entirely of the game’s cinematic cutscenes: polygonal men with jilted animation swinging swords, riding motorbikes and just generally being cool in the way that only 90’s media could feign. As easy as it is to look back on it and laugh, it’s also easy to forget that, at the time, this was groundbreaking stuff.

Final Fantasy 7 wasn’t the first game to feature FMV technology (that honour goes to Nintendo’s Wild Gunman, a whole 23 years earlier), or even the first to be recognised for it (although admittedly, Night Trap, Dragon’s Lair and Sewer Shark were not-so-good on home-consoles), but it did introduce a Hollywood sensibility to experiences that had previously been riding high on the crest of utter cheese. FF7’s cutscenes were overwhelmingly expensive, and it showed through in the quality; they were state-of-the-art for their time. The general mindset was that the game was essentially a a movie-within-a-game. The first bullet-point on the back of the PAL boxart advertises over ‘120 minutes of full-motion video’. Value for money, right?

FMV wasn’t the only big development, however. The switchover from the series’ long-standing character designer, Yoshitaka Amano, to newbie Tetsuya Nomura also lent a distinct look to the game, taking it in bold new directions, more in line with what the Western market was becoming accustomed to with the rapid growth of anime and manga in the West[1]. The change was reflected in the overall game design, removed from the traditional ‘swords and sorcery’ fare of earlier titles in the series, and towards a more futuristic vision, one that gave dated magical systems sci-fi infused constructs and eschewed smaller villages in favour of sprawling metropoles.

Under this new direction, the cyber/steam-punk visual ethos that would become synonymous with the game came to be praised as one of the its key selling points; Gamespot’s Greg Kasavin, for example, praised the visual design at the time as ‘beautiful in its grandeur and terrifying in its detail’, while IGN’s Jay Boor practically broke down in excitement, and got caught waxing lyrical about little else but the visual design for his review. Final Fantasy 7’s use of FMV, coupled with a compelling visual design, allowed it to catch the zeitgeist and ride it for the year following its release, giving developer Squaresoft (now known under the merger Square-Enix) a headstart when it came to marketing and branding.

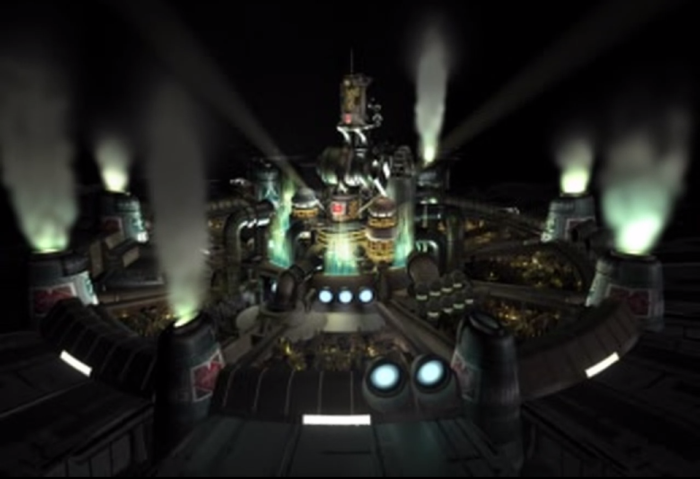

The iconic image of Midgar, captured here from the game’s opening FMV sequence, spearheaded the game’s marketing campaign.

Of course, Hollywood’s influence didn’t stop with the game’s visuals, but bled through into the narrative. Final Fantasy 7‘s opening sequence – a lengthy primer that threw players into the midst of a terrorist plot to bomb several power reactors – carried the pace of a Michael Bay film, propelling its player into an experience that was never shy to rest on spectacle. Yet as it turns out, it also wasn’t dumb. As if to ease people into the ride, both visually and thematically, this section was a succinct representation of the themes to come – economical storytelling buried in the guise of bombast.

The initial area – Midgar, an impoverished industrial city – sets out a distinct template, incorporating stark, metallic designs; slums constructed out of corrugated iron and bolted car parts. As overused as the ‘dystopian industrial city’ may be, FF7 was one of the first titles to realize it in detail. Thanks to the Playstation’s then-impressive horsepower, Midgar came alive. Even something as simple as developments in disc-space and storage allowed the game to feature more dialogue and better character models, enabling the player to converse with fleshed out characters clearly defined by their surroundings; to play witness to a culture formed in the cold, dark underbelly of the world. Back then, FF7‘s unprecedented interactive portrayal of poverty was all that was needed to engender interest in the ensuing narrative, spurred by game’s beginnings at rock-bottom.

The focus of the game’s initial section is a greedy conglomerate known as Shinra Energy, its headquarters a towering skyscraper overseeing the segmented slums of Midgar, and it’s in here that we’re introduced to one of the most divisive aspects of the game: its (sub)text.

In a nutshell, Final Fantasy 7‘s story concerns itself with a planet in decline, being bled – quite literally – dry by corporations like Shinra, who are harvesting ‘Mako’ energy, a green substance that’s composed of the life force of all living beings on the planet, and burning it for fuel. The player is placed in the role of Cloud Strife, an angst-ridden soldier with a shady past, who assists a group of militant eco-warriors. If you think that all sounds fairly heavy-handed, well, it kind of is.

The whole thing is a great big, broad whopper of a metaphor, dealing with the evils of Big Oil, corporate statism, and religious zealotry, wrapped up in a Native American-tinged tale of peace and love on earth. If I’m perfectly honest, I love the whole thing even more for it – heavy-handed or not, FF7 is so clear in its aims that I find it hard to criticise the naiveté with which approaches a lot of its concepts. That said, it’s not hard to see how the game’s narrative broad-strokes could be construed as adolescent, and those who don’t share my unashamed love for the game will probably fall foul of its trappings. For anyone returning to the game these days, the painfully obvious subtext will be one of its most off-putting aspects.

Although mileage will vary, and for me, a bit of heavy-handedness isn’t such a bad thing. FF7 is such a lengthy experience that it covers a lot of secondary ground within its side-stories; more concentrated themes, like those of loss and Old World discovery, themes that are ironically more fully-realised. It may not stand on par with the great mainstream chin-scratchers that would follow, but it took a broad leap in the right direction, and gave videogaming an intellectual jump-start going forward into the millennium.

FF7’s pre-rendered backgrounds not only looked pretty, but also sidestepped a lot of the Playstation’s limitations. It was practically limitless in scope.

So it was pretty, it dared to have a message, and it had FMV – but what I’ve failed to mention is that Final Fantasy 7 was a great game in its own right. There’s no question that its visual styling and ‘grown-up’ story brought in the sales, but the game itself thrived independent of the sum of its parts: it was (and arguably, still is) just fun. To this day FF7 remains overwhelmingly rich, brimming with interwoven systems and mechanics, and an emphasis on player freedom, giving way to a staggering number of diversions and secrets. Strip away the visual design and flashy cinematics, and it still has a lot going for it.

The base gameplay is standard turn-based fare, a race from point A to point B to kill the boss and advance the story. If the player walks around too much in a hostile area, the screen goes ‘whoosh’, and they are thrown into a tactical game of wits against any number of themed bad guys, taking turns to claw at each other’s delicates. Outside of battle, the player is free to explore the ‘world map’, a sprawling collection of islands, each with their own secondary landmarks and cities to visit, each with their own set of diversions, from the simple act of kicking a football around to the surprising depths of a self-contained, functional RTS. There’s a ridiculously large amount of variety in FF7’s world, which perhaps explains how it managed to hold the attention of so many for the fifty-plus hours it takes to beat.

Upgrading and optimising your team of fighters is a game of spreadsheets into itself, and even the core narrative repeatedly gives way to new systems, from a frustratingly hard snowboarding segment, to an entire section that tasks the player with cross-dressing to the best of their ability in order to woo a rich old tycoon. There are optional bosses, one-off opportunities to snag rare goodies, two secret characters waiting in the wings, and a seemingly never-ending sub-quest revolving around breeding and racing Chocobos (the series’ stalwart mounted transport), and that’s just scratching the surface. When it came out, the sheer depth of content ensured that everyone had a story to tell – a secret to share – and it succeeded in turning Final Fantasy 7 into the ideal underground ‘water cooler’ game.

Although in retrospect, the first five hour’s worth (!) of battle segments can be slow and frustrating, a problem common in JRPGs, and one of the main hurdles newcomers to the game will face.

These water-cooler conversations were just as vital to FF7‘s popularity as the TV spots and newspaper coverage. At the heart of the discussion lay videogaming’s very own ‘rosebud’ or ‘he was a ghost all along’ moment, derided and worshiped in equal measure: the death of Aeris. Aeris is a key player in the game’s earlier events, presented as a kind-spirited, pure-hearted romantic interest for Cloud, and through a number of simultaneously heart-warming and disturbing sequences, she’s presented as one of the core members of the player’s group of rag-tag vagabonds. About a third of the way into the game however, she’s (quite literally) cut down by the game’s emerging villain, the maniacal super-soldier Sephiroth.

Such was people’s love for Aeris that, to this very day, fans still find it necessary to scour the game’s files, searching for a way to keep her alive, and it’s rare to find any discussion of the game that doesn’t eventually spiral into a collective mourning over the character.

In the broader community, I’m aware that there’s a lot of scorn held for the Aeris death scene these days; it’s viewed as a juvenile attempt to tug at the player’s heartstrings, and there no doubt playing it today that the impact of the scene is significantly reduced. In an age where Call of Duty kills the player every five minutes, it’s hard to be shocked by Final Fantasy 7’s classic twist, especially when the game’s dated visuals and shoddy translation (more on that later) declare a fair amount of the scene dead-on-arrival.

Aeris’ killer, Sephiroth, has become almost as iconic as the game itself, and with good reason. His last-act ascent into godhood is perhaps one of the most notable ‘power corrupts’ parables told in videogaming.

It may not have been the first game to introduce an emotional twist, and it wasn’t even the first game to kill off a key character. It was, however, the first game that encouraged people to care. The effectiveness of her role in the narrative is debatable, but it’s worth remembering that this is an RPG, and as such, it’s entirely possible that players could become reliant on Aeris from a gameplay standpoint.

Her role as a medic is no coincidence; by design, the game goads its player into accepting her as a party member, lulling them into spending time upgrading her abilities and spending time building up strategies that hinge on her inclusion, before taking her away without notice. It’s a clever melding of gameplay and narrative; forcing genuine emotion on the player through abstract means. Aeris’ death was a milestone, if just because it proved that videogames could emotionally involve the player in a narrative, even if the player wasn’t necessarily involved with the characters within.

There are plenty of other memorable moments scattered throughout the game, too. Cloud’s incapacitation in the late-game encourages a switch of main-character, while the Shinra tower itself serves as an overt, interactive commentary on bureaucracy and corporate structure. One scene that always stands out for me, however, is a particularly dark moment in which Cloud, under the influence of mind control, is commanded to beat Aeris to death. What ensues is a pitch-perfect depiction of what is essentially domestic abuse – we’re forced to watch from a distance, disconnected, as Cloud proceeds to attack the object of his affection, a brutal attack that proves to be one of many developments showcasing FF7’s grasp over narrative and place.

Unless you play the game for yourself, you’ll find the vast majority of these stand-out moments have been lost to time – eclipsed by the more significant beats, like Aeris’ death – but it demonstrates exactly how FF7 managed to tap into the riskier side of fiction, and conjure up a story that was mature in ways that succeeded boob physics and splatter gore. FF7’s narrative is vast and complex in ways that videogaming has since collectively strived to emulate.

You could have loved her or hated her, but there’s no doubt that when this scene rolled around, you cared.

This is why it’s such a shame that each and every single one of these scenes is marred by the same problem – jilted translation. The localisation effort for FF7 is well-documented; Sony had originally intended to release a censored version in the US, in line with Nintendo’s previous localisations of the series, but following a community outcry decided to leave the ‘rough’ bits in, resulting in a ‘Teen’ age rating (and an ELSPA rating of 11+ in Europe). The decision was an important one, giving us the unadulterated version of the game that we all know and love today, and paving the way for the ‘thinking man’s’ blockbuster.

Unfortunately, the decision had little bearing over the quality of the translation itself. The original Playstation release was rife with grammatical errors and typos, in many cases devolving into gibberish (“This guy are sick”). Over the years, fan efforts have opted to fix the game’s PC release, giving us a version that sticks closer to the original Japanese, however, the fact stands that a mediocre translation effort left most with a sub-par version of the game, and the sub-par version is here to stay, warts and all.

For better and worse, Final Fantasy 7 has been enshrined as a cultural object, and thus is likely remains subject to modern scrutiny. For a modern audience, the translation is the least of the game’s problems. In particular, the game’s once-lauded animation has aged poorly – characters move with disconnected, grand gestures, more akin to a pantomime than a self-serious story of love and hope. Events like the aforementioned domestic abuse scene are near indistinguishable these days, as polygonal limbs fly left, right and centre in grand, sweeping motions. At the time, it was new and exciting, but in retrospect, it’s hard to see the game’s character models and animation as anything but ugly.

Similarly, the traditional JRPG has fallen out of favour in recent years. The mere presence of an ‘attack’ command is enough to make some modern gamers laugh, and places Final Fantasy 7 firmly within the ‘retro’ tradition. Like most Playstation games, it hasn’t aged well at all.

Of course, if there’s a catch-all saving grace, it’s the soundtrack. Long-standing series composer Nobuo Uematsu took the helm for what would be the defining moment of his career, crafting an emotionally engaging, melodic soundtrack to complement what he would identify as the game’s ‘human’ element. Funnily enough, however, he chose to ignore the Playstation’s use of CD technology – shying away from the ‘Red Book’ audio format that had become the norm for games on the system, and opting instead to stick with MIDI, operating off the Playstation’s internal sound-chip. As a result, the soundtrack had a distinct ‘retro’ sound to it, a much heavier, on-the-nose sound than the orchestral and instrumental pieces that other games on the system were gearing towards[2].

A better move couldn’t have been made, either, as FF7’s soundtrack has come to be recognised as one of videogaming’s finest. Tracks like ‘One Winged Angel’ have become enshrined in remix culture, while earlier this year; ‘Aerith’s[3] Theme’ reached number 16 in Classic FM’s yearly Hall of Fame, one of only two videogame songs ever to have made it onto the list. The entire soundtrack has received significant work over the years, with Uematsu himself helming a number of reinterpretations and orchestral works, and concerts showcasing the songs have become events unto themselves worldwide. There’s little I can say that will appropriately describe Uematsu’s work, so I’ll simply leave these links here.

The ‘Ruby Weapon’ battle – widely recognised as the game’s hardest challenge – is one of many optional tasks the player can choose to take on.

If all of this isn’t clue enough, Final Fantasy 7 managed to grab the attention of Joe Public and withstand the test of time because it exhibited a clear commitment to trying new things. At the time, the marketing was pitch-perfect, and the visuals were a clear indication of the Playstation’s capabilities. From a modern standpoint, its technological achievements may not have held strong, but the less aged elements; the soundtrack, the story, and to a lesser extent, the core gameplay, are still admirable. As much as I would hate to preach angry about the state of the modern videogame industry, I will say that I think Final Fantasy 7 has a lot to teach the current market. It took risks, and most of them paid off, tenfold.

For new players today, the game has a lot to offer as a history lesson, if not as much as a game itself, although it still remains highly playable. Like any great story, it welcomes anyone who wants to listen, and no number of graphical hang-ups or translation errors look likely to change that. If anything, it just requires a slight shift in expectations, because it’s unlikely to blow anyone away in the same way it did the masses back in 1997.

Nostalgia may have facilitated its continued presence in the gaming community’s collective psyche, but with good reason. Final Fantasy 7 was, and still is, an example of a great game sold well.

Final Fantasy 7 was recently re-released on PC in not-so glorious HD (the textures were, quite obviously, never designed for viewing on a high-resolution display). You can grab hold of it here, and you can replace the god-awful PC soundtrack with the Playstation version using Anxious Heart, here.

If you want to read more on the history of the game, Gek Siong Low has a great piece here, IGN’s Rus McLaughlin offers an alternate offering, here, and Tetsuya Nomura recently gave an interview to Famitsu regarding the game’s anniversary, translated here.

[1] Although funnily enough, one of the game’s biggest changes, the switchover to more ‘realistically’ proportioned characters, was bred of technical limitation, rather than design. The traditional standard for Final Fantasy 1 through 6 was to make characters ‘two heads’ tall, but when taken into 3D, it was discovered that this resulted in clipping issues, necessitating the slender designs in the final product.

[2] Debate has circled for a long time as to why Uematsu chose to avoid Red Book, however, most seem to agree that the switch to MIDI put a lot less strain on the Playstation’s CPU, allowing for smoother visuals, and was more in keeping with the series’ past.

[3] You may have noticed there are two different spellings of the name, Aeris and Aerith. As it turns out, the correct Japanese translation is ‘Aerith’, pronounced ‘Aeris’, but as a result of the dodgy translation, it was written down as ‘Aeris’ in the original release. The two are interchangeable.

Great retrospective, I think you really captured a lot of FF7’s lasting appeal. FF7 has always had enough substance to justify its longevity, even though its initial draw was a series of shiny objects built with piles of money. That said, a lot of looks back at the game come loaded with an apology for nostalgia; as if to say “I’m sorry that I like this thing even though its old.” I wonder if that has something to do with this medium being so consistently–and in my mind, harmfully–obsessed with newness.

It’s interesting how apologetic people become when they roll out the word “nostalgia” when talking about games. And while comparing video games to any other medium has its problems, you don’t see film critics talk about how shoddy Sergio Leone’s “Dollars” trilogy looks and sounds. Its aesthetics are due in large part to its time and place (and you’ve done a great job of summarizing the circumstances that led to many of its aesthetic choices), and while they might not be up to snuff to today’s triple A standards, FF7’s aesthetics are forever associated with that era in gaming, those novelties and revolutions. That’s not something to apologize for, it’s kind of special.

As for your recalling that scene when Cloud is possessed to attack Aeris, I never interpreted that as house abuse. I don’t know why, that’s obviously what it is, especially since the player adopts control over an invisible, child Cloud, screaming stop. It’s actually quite horrible and I never saw it. It makes sense, though. I’ve always seen Cloud as a really insecure, hapless kind of guy struggling with his gender. The way that he worships the masculine war heroes Sephiroth and Zack, his fatherless upbringing, the fact that he wields a massive sword between his legs. At the same time he’s really lonely, immature and socially incompetent. I think his whole arc follows his discovery that he’s not an Ubermensch and that that’s a good thing: those kind of men are dangerous or doomed. The spousal abuse allegory kind of fits in with that, but it’s got a lot more bite to it than I realized. The ability to read into FF7 makes it worth hanging onto, even while the sprites look like they’re made from Lego.

That’s the long version of this comment. The short version is “Thanks for the great article, keep up the good work!”

LikeLike

Hey Mark, thanks for the kind words! To be honest, I’m critical of anything I’ve written that’s more than a week old, so I’m flattered that you felt inclined to navigate this sprawling mass of text. You’re a braver man than I.

You raise a really interesting point regarding nostalgia, too. Personally, I think that videogaming is unique in that it tends to be a lot more reliant on trends and technology. The act of watching and interpreting a film has remained largely unchanged for the better part of a century; the visual language is the same now as it was with The Wizard of Oz a whole 74 years ago. In videogaming however, the language always seems to be in flux; only eight years ago, for example, I wouldn’t have been able to play and appreciate a cover-based shooter – an odd thought, considering how prevalent they are now.

Sergio Leone’s trilogy, on the other hand, still speaks the ‘modern’ cinematic language. It’s like going from The Last of Us to Gears of War: there’s a common ground. Go back more than ten years in gaming, however, and I think that our collective language has evolved so much that it’s more on par with returning from Pacific Rim to a zoetrope reel.

That said, I absolutely agree that FF7′s aesthetics are emblematic of a place and time, and that FF7 is more than worth hanging onto. Just because modern trends are divorced from FF7′s gameplay, it doesn’t necessarily mean that new players can’t appreciate it – or even grow to love it.

Ultimately, I think the apologetic tone of my article, and most out there on the web, stems from a position of insecurity. As a relatively new writer in a relatively new medium, it’s easy to be scared by the changes that have taken place in the last fifteen years. There’s always a fear that the reader won’t be able to connect with what you’re saying; and so it’s easy to sink into apologetics. If you preface a sincere comment with ‘at the time’ it removes culpability if the audience doesn’t understand.

I think it’s just a teething pain of games criticism. The gap in understanding between one gaming generation and the next is one issue out of hundreds unique to the medium, all of which are feeding brand new systems of thought and interpretation. As far as I’m concerned, it’s a bit of a mess, and it’s hard to know who you’re talking to at any given moment. Combine that with the fact that – in this case at least – most FF7 pieces are being written by relatively inexperienced twenty-somethings, and it becomes easier to understand why we may feel the need apologize for things when we don’t necessarily have to.

Luckily, we’re only getting better at it.

LikeLike

Good point. It’s hard not to feel compelled to apologize given that our parents (figurative and literal) are look so far down their noses at us. That most of us are in poverty and a few absurdly privileged people dictated the medium doesn’t do us any favours. Like I said, I apologize as much as anyone. Maybe it can’t be helped. That said, I agree that we’re getting better at: it’s something to continue working on. Anyway, thanks once again for the piece.

LikeLike

Pingback: One of Many Looks Back at Final Fantasy VII | bigtallwords

Pingback: Research. |

Pingback: Final Fantasy VII – Critical Distance

Pingback: Boss Rush Banter: Which Final Fantasy Game is Your Favorite?