(Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Fixed Camera Angle)

Eleven years ago, I had to give up on Silent Hill 2. Even under the direction of a friend – who informed me that he’d just found the ‘coolest game ever’ – I could barely make it past the game’s first ‘proper’ challenge: the labyrinthine apartment block that acts as its introduction (and an introduction which, for the record, dominated many a nightmare for years to come). Silent Hill 2 was eerie in a way that even the franchise’s long-running competitor, Resident Evil, couldn’t quite manage. It’s atmosphere was tangibly oppressive.

Driven by a desire to see the experience through, I returned to it again and again, each time beating my chest and throwing out countless hollow platitudes, taken by the belief that I could make the horror go away. Most of the time, I was wrong.

The platitudes never helped. Nor, for that matter, did opening all the curtains and playing the game in beaming sunlight. Eventually, however, I arrived at the game’s conclusion, and breathed a long-deserved sigh of relief.

At the time, I’d enjoyed it as a challenge; as a mark of bravery, but in retrospect it became just another one of those dumb games I’d played to pass the time before growing up. I’d appreciated it, if begrudgingly, for the countless hours it took to finish, but never really looked back; Silent Hill 2 became a footnote in the grander scheme of adolescence.

Cut to about two weeks ago, however, and I was once again sat at the game’s title screen – this time on PC – having decided to give it another run to see whether all those nightmares were justified. Cut to about an hour after that, and the game was shelved once more, set aside for a braver day.

If there’s one thing to be noted returning to Silent Hill 2 after ten years, it’s that it remains an unbelievably intimidating experience.

Having mostly forgotten the specifics of the game, the first thing to jump back at me was the soundtrack. Composed by Akira Yamaoka, it’s a muddy, grinding mess; a jumble of bassy synths, heavy breathing, and screeching machinery, occasionally broken up with a bit of light acoustic guitar. Far removed from the tired, wailing strings that have come to dominate the genre, Akira’s work blends the innocent romanticism of the American Northeast with something much more sinister, and the dissonance between the two creates a tension that never quite resides. The more I think about it, the more it sums up the game as a whole.

The titular Silent Hill is a place defined by its juxtapositions. The merging of an otherwise-innocent community with the unspeakable horrors of hell is hardly a revelation – Stephen King has written that book at least thirty times in his career alone, but here, the concept is brought kicking and screaming into the interactive format. The game’s narrative is one of the richest in videogaming — thanks in large part to the way in which it is rooted in the act of playing — and slides to great effect between the metaphorical and the literal without ever quite revealing itself.

At its core, Silent Hill 2 is a story of love and loss, but in a more bodily sense, tackling the ideas of sexual repression and low self-esteem that can stem from a life-shaking personal event. Silent Hill 2 doesn’t present a doomsday scenario, or contrive lore to explain its every creation scientifically; it doesn’t have a codex, or an encyclopaedia – it’s simply a story about a small group of people coming to terms with life, set in a town that gives them the means to do so. The Silent Hill franchise may have flown off the rails in trying to give the town global/universal/dimensional significance, but back when Silent Hill 2 came out, the idea was still pure, focused and personal – and all the better for it.

Silent Hill 2 throws its player into the shoes of James Sunderland, a troubled widower drawn to the titular town in the belief that his wife may still be alive there; despite the fact that he witnessed her death at the hands of cancer two years prior. As in the rest of the series, Silent Hill adapts itself to the worries of its protagonist, and it’s from here that the game progresses, funnelling James deeper into a literal manifestation of his own psyche in the search of answers. As a result, the town is heavily laden with symbolism; a compacted vision of his time with his wife, and little is left to cutscenes or text dumps other than the key story beats. In Silent Hill 2, the town is the story, and we’re guided into assumptions based on James’ visions of Silent Hill and his reactions to them.

All the while, there are four additional characters roaming the town’s streets, each more unhinged than the last, each plagued by their own set of horrors resulting from their own – and James’ – grievances. If there’s one thing that struck me about the whole experience, it’s how concentrated it all is. As large as the playable area of Silent Hill may seem at first, in the context of the story progression, it’s surprisingly small. As is typical of survival horror, it’s entirely possible that you could blow through the game in just a few hours and be done with it, and where Silent Hill finds its value is in the attention to detail along the way. Every character is drenched in their own subset of imagery – their own themes; in the audio, the video, and the narrative – and it all comes together to form a cohesive picture of grief, albeit one painted in blood and tears.

The game’s prolonged stop at Silent Hill’s decrepit hospital, for example, is no coincidence. The increasingly begrimed walls and images of death and decay evolve and spread like the cancer that killed James’ wife, and come to represent his internalisation of the few visits to the building in which he would eventually watch her die. In this regard, the hospital serves as the game’s thematic core, and the rest of the experience spirals outwards from it, taking its players to key areas from its characters’ pasts in order to explore the woes of love, loss and regret in explicitly physical terms. Silent Hill 2’s narrative continually proves itself to be darkly intelligent, much more so than I remembered.

If the dichotomy between the doe-eyed James and the horrifying environment of his mind’s creation wasn’t enough; Maria (pictured) further explores the duality of the human psyche. She is a sinister, sexual doppelganger of his wife, Mary.

If you’ve read my bit on the recent outbreak of indie horror games, then it should come as no surprise to learn that Silent Hill 2 isn’t even a fun game; it’s an oppressive glimpse into humanity’s immoral tendencies, and the overall experience of playing is topped with a relentlessly unforgiving atmosphere reflecting this grim outlook. Movement is deliberately slow and laboured, placing a greater emphasis on smaller encounters, and – following the precedent set by the first game’s technical limitations – the whole thing is drenched in fog and darkness, so much so that you’re lucky to ever see more than a few feet in front of your face, even when equipped with a flashlight.

That last point may prove particularly irksome to some, too, considering that there are some genuinely unsettling creatures lurking behind the fog, topping out at a moving, writhing depiction of incestuous rape. As much as I feel like I need a shower after typing that, it’s contextualised within the narrative and subtle enough that it comes across as more sophisticated than the shock value of its description would suggest (but that still doesn’t make it any less unpleasant to witness). Silent Hill 2 is a horror game with modesty – walls drip with blood, sure, but in moderation; and while a lot of its scares may be tried-and-tested in the bigger picture of the genre, it paces and delivers them in such a way that they seem new. Nothing appears contrived for shock value, or created purely to look as grotesque as possible, and as a result, it doesn’t give us anything quite as ridiculous as Resident Evil’s shoulder-eyeball antics.

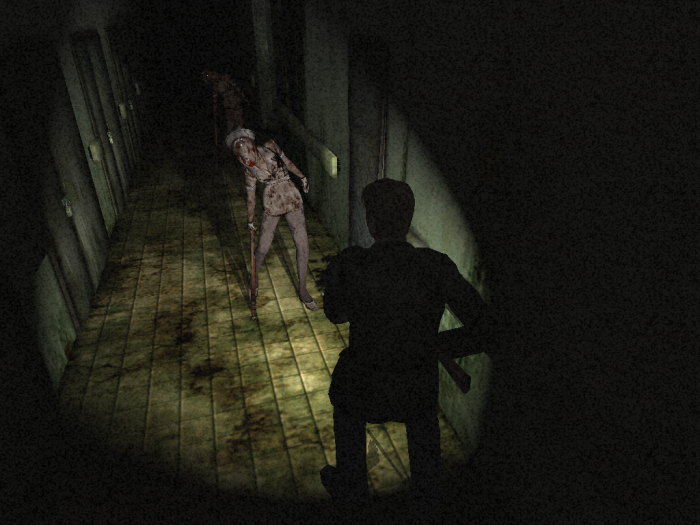

The man responsible for this decision, monster designer Masahiro Ito, has made clear that his ‘basic idea in creating the monsters of Silent Hill 2 was to give them a human aspect’, and it’s this human aspect, and it’s concentrated removal, that keeps Silent Hill 2 grounded and believable, even in its most bizarre moments. The aforementioned hospital environment, for example, introduces its own monstrosities to the fold, the now-stalwart ‘bubblehead’ nurses; silent, faceless apparitions of the building’s former workers. As what can be seen as the beginning of the game’s ‘deeper’ exploration of James’ anxieties, the nurses are, in a strange turn from the game’s previous offerings, somewhat sexy, sporting short skirts and coyly exposed cleavage – rotten and bloodied, of course, but still conforming to a physical ideal atypical of standard horror creations.

As character artist Takayoshi Sato explains, ‘everybody is thinking and concerned about sex and death, [so we] tried to mix erotic essence…this is a kind of a visual and a core concept’. The twisting, faceless nurses that inhabit the hospital’s wards exemplify this ‘erotic essence’, embodying James’ sexual frustrations during his wife’s illness, and a guilt over his natural sexual urges. In speaking on the ‘main factors that evoke fear’, Sato expresses humanities reluctance ‘to see concealed their true-self’, a fear made all-too clear in James’ visions of the nurses (and the rest of the game’s creatures, for that matter).

Again, it remains impressive just how concentrated Silent Hill 2 proves to be, reigning in videogaming’s tendencies to aim for the stars and instead portraying something more realistic and relatable. Given this microscopic focus on detail, even something as simple as James’ radio – the game’s analog to a radar, which floods with static as enemies come closer – serves as a firm symbolic statement of communication, a means through which James can converse with his subconscious, and in gameplay terms, avoid the negative manifestations of his own mind that threaten this conversational ability. When it comes to the surreal and the weird, it helps if there’s some underlying support holding everything together, a thematic backbone that can make the inexplicable explicable, and in this regard, Silent Hill 2 never strays too far from its own support.

One of the biggest surprises for me was how nicely the game holds up for its age. Sure, it’s still positioned in that awkward PS2-era bracket where animations and geometry can come across stiff and flat, but it’s sure enough in its art direction and texture work that it ignores system limitations, in a similar vein to Resident Evil 4 or Shadow of the Colossus.

The denizens of Silent Hill are as grotesque and gnarled as ever, from the mechanical spiders that roam its streets, to ‘those guys with pyramids on their heads’; visually, Silent Hill 2 still stands its ground. I suppose polygon count doesn’t stand for much when ninety percent of your creations are twitching masses of flesh. To this day, the bizarre spasms of an approaching ghoul are still enough to give me a severe case of the heebie-jeebies, probably even more so now that I understand what they’re meant to represent.

Complementing this, Silent Hill 2 tries it’s hardest to shy away from the Resident Evil/Dead Space ‘monster in the closet’ approach. Creepy as they may be, enemies are sparse in Silent Hill, especially towards the game’s earlier half; and if you’re familiar with the genre, that can end up being the scariest thing about Silent Hill 2. Subtle, one-off audio cues are thrown at you to brilliant effect, from the sudden, cut-off wail of a woman’s scream coming from a toilet cubicle you just checked, to the thunderous, approaching footsteps of something better left alone approaching you in the darkness, a vast majority of which might not ever culminate in any actual action. ‘Pyramid Head’, the game’s closest analog to an antagonist, serves up the occasional ‘boo’ scare, but almost everything else is left within the mind, and it pays off tenfold.

There’s one part in particular that cemented Silent Hill 2’s greatness for me and, like the rest of the game, it went largely unannounced. Through a lovably contrived twist of fate, there’s a point towards the game’s later half in which the player is left defenseless, forced to roam Silent Hill’s familiar, twisted halls with the training wheels off. It’s a segment that’s just about as mischievously evil as you’d imagine, leaving the player with no option but to crawl into the corner, adopt the foetal position and mash every button on the controller in an attempt to bite at the ankles of their aggressors, while they take their opportunity to return in kind. It’s spooky as they come, and especially clever in the way that it mixes up enemy spawning patterns, meaning that even when you decide to kick the controller into ‘flail and run around screaming’ mode, you still can’t quite predict how to get past the ghouls in your way.

For me, the most chilling and game-defining moment was an unassuming corridor just seconds into that section; a simple ‘L’-bend that branched off into a small corridor with no purpose, other than to look intimidating. If the screenshots dashed around the page aren’t enough indication, Silent Hill 2’s particular blend of third-person action is dictated by fixed camera angles, the kind that could instil a sense of claustrophobia in an industrial mine-worker. As anti-climactic as it may sound, that single corridor, obscured by a shifty camera, and completely inoffensive in the grand scheme of Silent Hill’s horrors, pushed me to my absolute limits. Building up the courage to progress took me longer than I’d care to admit.

It’s because of cases like these that, come any discussion concerning Silent Hill, or the earlier Resident Evil games (or in some rare circles, Alone in the Dark or Dino Crisis), I’ll always be the first to defend fixed camera angles, and by extension, ‘tank’ controls.

While the sole bastion of most popular videogame writing is the vacuous entity known only as ‘the gameplay’, I’m a firm believer that, unless you’re looking to make an ‘arcade’ style game wherein snappy mechanics sit above all else (and don’t get me wrong, there’s nothing wrong with that), the developer’s first concern should be the desired experience –the story, the feel; and the gameplay should work in favour of this experience.

Especially in horror – gameplay decisions that aren’t necessarily conducive to the arcade ideal of ‘fun’ shouldn’t be seen as bad things. Tank controls might be a misstep for a more action-oriented game, but in horror, they play perfectly into the feeling of powerlessness and tension that are the staples of the genre. The fixed camera angle isn’t practical – heck, it isn’t even realistic – but then, neither is using a £20 hunk of plastic to manoeuvre around the world.

The problem with chasing realism in videogames is ultimately: until we reach that zenith of an immersive virtual reality, we’re still just guys and gals sat on our asses in front of a row of buttons. A realistic horror experience, ironically enough, isn’t a horrifying one in videogaming, because we’ll always be that one step removed from the ‘reality’ presented. More responsive controls might help us better approximate real human movement, but they’ve killed more experiences than I can count. Call me old-fashioned, but I think it’s better that we handicap ourselves with restrictive styles like the fixed camera angle if it conveys the fear of a situation more appropriately than pin-point, Halo controls. There’s a reason why Amnesia’s sanity effects spat in the face of the precision of a keyboard and mouse.

Silent Hill 2 has an odd evolution of the fixed camera angle, one that can obscure vital information about what’s to come, and trick the mind into seeing things that aren’t there. It has sluggish controls, and makes turning corners in a pinch much harder than it would be in any other game – essentially condemning the player to a slew of stressful encounters, and slowing the game’s pace down to a crawl. By most conceivable metrics, Silent Hill 2’s entire system of control seems regressive – and yet this only works in its favour.

It may seem unnecessary to dedicate so much real estate to one small feature, especially one as debatable as this game’s cumbersome controls, but as I’ve come to find, it’s these little things that prove most endearing in Silent Hill 2, and videogaming as a whole; the unannounced details that creep up on you and hit you where you least expect it. A lot of Silent Hill 2’s design decisions may seem ass-backwards when starting out, but I found myself agreeing with them more and more as the experience went on, to the point at which I’d say it couldn’t have been done any other way. Games like Dead Space and Condemned, as fond as I am of those particular series, fall into one of the worst traps of modern horror, in that they grant their players too much power over their horror elements – they don’t take enough risks, and as a result, announce all of their scares

In Silent Hill 2 this idea is completely inverted – it may occasionally present you with an ammo dump or a ‘keep out’ sign so obvious, that you can’t help but find yourself on edge. It might throw a storage cupboard into view, full of goodies, then funnel you into a wide, open space- and leave you free of enemies for upwards of ten minutes, left to suffer from your own anxieties and assumptions. It’s a game where the scares are derived from the player’s knowledge of the medium, in tandem with the developer’s understanding of interactivity, rather than some tired Hollywood ideal of what should go bump in the night. Very few punches are telegraphed in Silent Hill 2, and it helps keep the player on edge; and draws attention to some of the smaller details, fostering a sense of paranoia than only grows as the game progresses. You probably won’t find the ‘corridor of doom’ as terrifying as I did, but I have no doubt that there’ll be something else in this game that will eventually get to you; whether it be a shivering wall of creatures or something as simple as a flickering light.

Again, it’s these sorts of juxtapositions that define the game; bad ideas made good, the innocent perverted, and perhaps most important of all, a videogame made clever. If you were like me, and never quite got around to putting the lid on this game – or better yet, if you’ve never played it at all: pick up a copy on PS2 or PC (not the god-awful HD port) and set aside some time in the dark to get into this one, because it remains one of the most relentlessly atmospheric and rewardingly cerebral games ever made.

I took some time away from this little write-up before posting, just to make sure I’d support myself in such a bold closing statement, but heck, I can’t think of a game more set in its aims, and more accomplished in delivery. It has its quirks sure, but when it comes to horror in videogames Silent Hill 2 is perfect.

If you want to find out more about Silent Hill 2, then you can view the once-DVD-exclusive ‘Making Of’ here (transcribed here), or head on over to Silent Hill Memories, a series-specific site that borders on the fanatical, in the best possible way. Shamus Young has a rather neat plot analysis over on his personal site and Twin Perfect have collected every reason not to buy the HD collection as part of their season-long look at the series. Failing that, Wikipedia is always just a click away, assuming you’re willing to brave a potential mugging by Jimmy Wales.

Reblogged this on Inklings and devlings.

LikeLike